BIG IDEA:

THE LEADERSHIP TRANSITION FOR THE NEW GENERATION THAT WILL ENTER THE PROMISED LAND (DESPITE THEIR CONTINUING CONTENDING AND COMPLAINING) REQUIRES THE DEATH OF ITS FAILED LEADERS

INTRODUCTION:

This is a sad chapter indeed. Sandwiched between the accounts of the deaths of Miriam and Aaron, we have the record of the disqualifying failure of Moses at the waters of Meribah and the obstinate refusal of Edom to grant safe passage. Despite a track record of significant leadership success, at the end of the day we find that Miriam and Aaron and Moses are unable to “Finish Strong” and are shut out of the opportunity of entering the Promised Land. However, the Lord remains gracious and merciful and faithful to His covenant promises and transfers priestly leadership to Eleazar as preparations begin for the coming invasion of Canaan.

Gordon Wenham: From Kadesh to the plains of Moab (20:1–22:1)

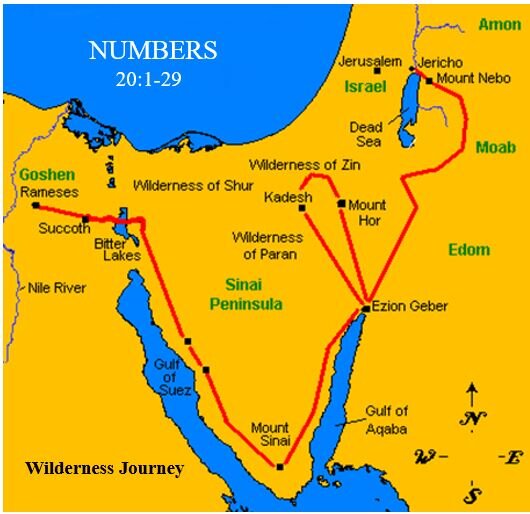

The brief notice of the death of Miriam (20:1) introduces the third and last travel narrative in Exodus–Numbers. The first deals with the journey from the Red Sea to Sinai (Exod. 13–19); the second covers that from Sinai to Kadesh (Num. 11–12), while this final one summarizes the journeyings from Kadesh to Transjordan (Num. 20–21). As was noted in the Introduction, certain motifs occur in all three travelogues, e.g. battles with enemies (Exod. 14; 17:8–16; Num. 14:45; 21:1–35), complaints about the lack of food and water and its miraculous provision (Exod. 16–17; Num. 11; 20:2–13), the need for faith (Exod. 14:31; Num. 14:11; 20:12), the role of Moses, Aaron and Miriam (Exod. 15:20–21; Num. 12; 20:1). . .

But the third journey proceeds quite differently. It begins in gloom and ends on a note of subdued but real jubilation. Chapter 20 records the deaths of Miriam and Aaron, and Moses’ unbelief that shut him out of Canaan. But this is followed in chapter 21, by victory at Hormah, where years earlier Israel had been defeated (cf. 14:45), and further victories over Sihon, king of Heshbon, and Og, king of Bashan, are accompanied by short songs of celebration (21:14–15, 17–18, 27–30). These three victories and their songs recall the first and greatest victory over Egypt by the Red Sea that Moses and Miriam had hailed in Exodus 15. Thus this final travel narrative inverts the patterns found in the earlier two; whereas they recount triumphs that turned into tragedy, this tells of tragedy that ends in triumph and a reawakened hope of entry into the promised land.

Raymond Brown: The chapter opens and closes with a family bereavement. Within four months (20:1; 33:38), Moses lost both his sister and his brother. Sadly, since the departure from Egypt both Miriam and Aaron had featured in discouraging events, and the Scripture makes no secret of their alarming disloyalty (12:1–16). Yet, despite their mistakes, they had been his life-long partners, to say nothing of their devoted family ties. At the beginning of his life Miriam had been a protective sister, and later Aaron had proved a supportive brother. To be suddenly bereft of their help and companionship at such a crucial stage in the long journey must have been a severe loss.

Roy Gane: This is a sad chapter. The deaths of Miriam at the beginning (20:1) and Aaron at the end (20:22–29) frame a dispute of the Israelites over water at Kadesh (20:2–13) and Edomite refusal to let the Israelites pass from Kadesh through their territory (20:14–21). The chapter is united by the location at Kadesh and the fact that Aaron dies at Mount Hor on the way around Edom for his failure with Moses regarding the water (20:24). The gloom of this chapter is only implicitly relieved by the fact that Israel and its high priestly office survive to trudge on toward better days.

MacArthur: These chapters (20-22) record the beginning of the transition from the old generation (represented by Miriam and Aaron) to the new generation (represented by Eleazar). Geographically, Israel moves from Kadesh (20:1) to the plains of Moab (22:1) from where the conquest of the Land would be launched. There is an interval of 37 years between 19:22 and 20:1.

(:1) PROLOGUE — DEATH OF MIRIAM MARKS THE BEGINNING OF LEADERSHIP TRANSITION

“Then the sons of Israel, the whole congregation, came to the wilderness of Zin in the first month; and the people stayed at Kadesh. Now Miriam died there and was buried there.”

Timothy Ashley: The note simply records her death as that of the first of the old-generation leaders. Perhaps the author felt it important to mention her death here before the events of vv. 2–13. Although the text does not mention mourning (cf. the death of Aaron, 20:24; and of Moses, Deut. 34:8), this does not mean that there was no period of mourning for her. Perhaps the only tradition available concerned the fact that she died at Kadesh. Miriam was last mentioned in 12:1–16. She had been preeminent in the rebellion of Israel’s leaders against Moses (Aaron, Korah, and others followed). Rebellion against God brings death.

Dennis Cole: Miriam’s death and burial is reported with simple reverence. She was a leader among the Israelites, a prophetess and songstress (Exod 15:20–21), sister of the divinely chosen high priest and prophetic leader of the nation, who demonstrated her compassionate character soon after Moses was born (Exod 2:4–9). Miriam was gone, the only woman whose death has been remembered from that generation. The love Moses had for Miriam was demonstrated when she was struck with a leprous skin disease after she challenged Moses’ authority (Num 12:1–13). Appalled by what he saw affecting his beloved sister, he dramatically cried out for the Lord to heal her. Then in honor of Miriam, the nation delayed its march for the required period of seven days for her purification before it continued on its divinely led journey from Hazeroth to the Paran Wilderness. What effect Miriam’s death had on Moses’ rebellion in the verses that follow one can only speculate. I would suggest that these events are juxtapositioned purposefully in the text, and were thus at least a contributing factor to the prophet’s demise. The death of Moses’ dear sister Miriam may have caused the prophet to enter a period of depression or even despair, which might have led him to respond so negatively in the following account.

I. (:2-13) GRUMBLING AND GLORY-GRABBING AT THE WATERS OF MERIBAH

A. (:2-5) Grumbling by the People in Questioning the Goodness and Faithfulness of God’s Provision

1. (:2) Antagonism of Deprivation

“And there was no water for the congregation;

and they assembled themselves against Moses and Aaron.”

Gordon Wenham: Particularly remarkable, though, is this story’s similarity with that recorded in Exodus 17:1–7, the first occasion when Israel complained about a total lack of water. Both times the people contended with Moses, and asked Why did you bring us up out of Egypt? Both times Moses is told to take a rod and use it to bring water out of the rock. Both places are called as a result of the incident Meribah (13).

2. (:3-5) Arguments of Contention

“The people thus contended with Moses and spoke, saying,”

Raymond Brown: They opposed his servants. Instead of approaching their leaders as effective intercessors, the crowds treated them as moral scapegoats. Throughout the years, Moses and Aaron had had a bad time of it with this unhappy mob, and the grounds of their complaint now were much the same: things had been infinitely better in their idealized past. Their present diet was detestable and life’s future prospects were agonizing (21:4–5). The crowd gathered in opposition to Moses and Aaron. Ostensibly, this unhappy congregation quarreled with Moses (3) but, in reality, they were complaining against God.

One “If Only” argument and Two “Why” arguments:

a. (:3) If Only We Had Perished Already –

Questioning God’s Love

“If only we had perished

when our brothers perished before the LORD!”

Raymond Brown: Far from being humbled and chastened by the experience of the earlier rebels, they wished it had happened to them.

b. (:4) Why Have You Led Us Into This God-Forsaken Wilderness –

Questioning God’s Goodness

“Why then have you brought the LORD’s assembly

into this wilderness, for us and our beasts to die here?”

Iain Duguid: Two familiar patterns of sin in their complaint are problems for us as well: catastrophizing and blame-shifting. Catastrophizing means that we paint our situation in far darker colors than is really warranted. Was their situation in the wilderness really a fate worse than death by fire (v. 3)? They may have been thirsty and missing some of their favorite foods, but the Lord had supplied those needs before, and he could do it again. They weren’t really as bad off as they alleged—and often neither are we. Isn’t it amazing how full of woe we can be while we are still healthy, surrounded by a family that loves us, with a roof over our heads? If we lack anything, is it too hard for the Lord to supply what we need? Instead of catastrophizing and anticipating the worst, we need to take our concerns to the Lord and trust in his goodness and power to provide for us in the situation.

c. (:5) Why Have You Misled Us with False Promises –

Questioning God’s Faithfulness

“And why have you made us come up from Egypt, to bring us in to this wretched place?

It is not a place of grain or figs or vines or pomegranates, nor is there water to drink.”

Raymond Brown: They frequently recalled the luxurious meals of Egypt (11:5; 16:13) or visualized the attractive diet of Canaan (16:14), and saw both in stark contrast to their barren wilderness experience. Longing for what we want, we ignore what we have received. They forgot his mighty acts of deliverance. They ignored the daily evidence of his presence and the nightly assurance of his protection. They despised his unfailing gift of nourishing food, the ready supply of necessary water and restful locations where they enjoyed shelter. They marginalized his immense kindness in keeping them free from sickness and disease, even protecting their feet from discomfort and their clothing from wearing out. During those long years in the desert, they had ‘not lacked anything’. But they were not remotely grateful. Moses and Aaron listened to the complaints of the multitude until they could bear it no longer. They went from the company of a disgruntled people into the presence of a holy God.

B. (:6-11) Glory-Grabbing by Moses Out of Frustration for Persistent Contention

1. (:6a) Another Face Plant

“Then Moses and Aaron came in from the presence of the assembly

to the doorway of the tent of meeting, and fell on their faces.”

2. (:6b) Another Appearance of the Glory of God

“Then the glory of the LORD appeared to them;”

3. (:7-8) Detailed Instructions on How to Obtain Water

“and the LORD spoke to Moses, saying, 8 ‘Take the rod; and you and your brother Aaron assemble the congregation and speak to the rock before their eyes, that it may yield its water. You shall thus bring forth water for them out of the rock and let the congregation and their beasts drink.’”

Timothy Ashley: Is it Aaron’s rod that budded (17:23 [Eng. 8]) or Moses’ own rod with which he, e.g., struck the Nile in Egypt (Exod. 7:17, 20) and the rock at Rephidim (Exod. 17:6)? The most logical choice would seem to be the former, since the phrase from the presence of Yahweh (millip̄nê YHWH) in v. 9 is probably a direct reference to the fact that this rod had been placed “before Yahweh” (lip̄nê YHWH) and had been taken “from Yahweh’s presence” (millip̄nê YHWH) and replaced “before the testimony” (lip̄nê hā‘ēḏûṯ) in the tent of meeting (17:22, 24–25 [Eng. 7, 9–10]). The question of whose rod it is would probably not have come up were it not called his (Moses’) rod in v. 11. This phrase implies only that Moses was in possession of the rod. . .

The word for rock here (selaʿ) is different from that of Exod. 17, and indicates a cliff or crag. Most interpret the fact that the noun has the definite article to indicate that it was well known.

4. (:9-11) Faulty Execution of the Lord’s Instructions

a. (:9-10a) Starts Out with Obedience

“So Moses took the rod from before the LORD,

just as He had commanded him;

and Moses and Aaron gathered the assembly before the rock.”

b. (:10) Continues with Angry Frustration and Glory Grabbing

“And he said to them, ‘Listen now, you rebels; shall we bring forth water for you out of this rock?’”

Raymond Brown: but, instead of speaking to the rock, he spoke to the people.

Iain Duguid: Not only did Moses set himself up as the people’s judge, he also set himself (and Aaron) up as their deliverers. He said, “Shall we bring water for you out of this rock?” (v. 10). Then he struck the rock twice, as if it were his action that brought forth the water. Who provided water from the rock for the people? It was the Lord, of course. In his frustration with the people, Moses was drawn into the same mind-set they had, forgetting the Lord’s presence and power and acting as if everything were up to him. Moses presented himself as if he were a pagan magician with the ability to manipulate the gods to do his bidding. . .

In setting himself up as judge and deliverer of the people, Moses was demonstrating that he too had failed to learn from the past. That same self-exalting attitude was exactly what he had demonstrated when he first recognized the plight of his people when he was living as a prince in Pharaoh’s court. At that time, Moses saw an Egyptian beating an Israelite, and he intervened and killed the Egyptian (Exodus 2:11, 12). The next day he saw two of his fellow Israelites fighting and tried to rebuke the one who was in the wrong. The man’s response was, “Who made you a prince and a judge over us?” (Exodus 2:14). In other words, as a youth in Egypt Moses had been trying to judge and deliver his people in his own strength without a commission from the Lord. That attempt had ended in abject failure. Now, many years later, Moses had reverted once again to that old pattern of self-trust, judging the people in his own wisdom and trying to deliver them through his own acts, with similar results.

c. (:11) Finishes with Costly Rebellion

“Then Moses lifted up his hand and struck the rock twice with his rod; and water came forth abundantly, and the congregation and their beasts drank.”

Gordon Wenham: Faith is the correct response to God’s word, whether it is a word of promise or a word of command. Psalm 119:66 can say ‘I believe in thy commandments’. The opposite of faith is rebellion or disobedience (e.g. Deut. 9:23; 2 Kgs 17:14). Thus Moses’ failure to carry out the Lord’s instructions precisely was as much an act of unbelief as the people’s failure to trust God’s promises instead of the spies’ pessimistic reports (Num. 14:11). Both were punished by exclusion from the land of promise. Because Aaron helped Moses (8, 10), he received the same sentence (12).

Moses’ unbelief was compounded by his anger, expressed in his remarks to the people (10), ‘he spoke words that were rash’ (Ps. 106:33), and by his striking the rock twice (11). De Vaulx suggests that there was an element of sacrilege in striking the rock, for it symbolized God. The people were gathered in a solemn assembly (10) before it as though before the ark or tent of meeting, and Moses was told to speak to it (8, neb). An additional argument in favour of this suggestion is that elsewhere God is often likened to a rock (e.g. Pss. 18:2; 31:3; 42:9, etc.). This understanding of the rock closely corresponds to that of the targums, and of Paul, who says ‘they drank from the supernatural Rock which followed them, and the Rock was Christ’ (1 Cor. 10:4).

In disobeying instructions and showing no respect for the symbol of God’s presence, Moses failed to sanctify God; that means he did not acknowledge publicly his purity and unapproachability. When unholy men approach God, he shows himself holy by immediate or delayed judgment (13; cf. Lev. 10:3). Whereas Aaron’s sons died on the spot for offering incense that was not commanded, Moses and Aaron received a lighter sentence: they would not be allowed to lead the people into the land which I have given them (12). Nevertheless, this was enough to vindicate God’s holiness (13). This last phrase he showed himself holy (wayyiqqādēš) is evidently a play on the word Kadesh (qādēš, ‘holy person’ or ‘holy place’), in the vicinity of which this episode took place.

Raymond Brown: they misused God’s gifts. Moses and Aaron were equipped by the Lord with two specific gifts: leadership and communication. Here, they misused the gift of leadership. As the Lord’s servants, they were meant to be models of submissive obedience. The people expected them to do everything just as he commanded. In the teaching of Numbers, nothing is more important than obeying what God says, and here was Moses at the end of his life failing to do exactly what he was told. In that moment, this great and gifted leader misused his gift of leadership and did what he wanted rather than what God demanded.

They also misused the gift of communication. Both men had spoken powerfully for God throughout their lifetime, and the great things the Lord said to them are preserved for us in Scripture. That day, at the rock face, Moses used the gift of speech to harangue the people rather than to exalt the Lord. ‘Instead of making the occasion a joyful manifestation of God’s effortless control over nature, they had turned it into a scene of bitter denunciation.’ The heedless crowd deserved to be called rebels, but that was not what the Lord wanted them to hear that day. A visible display of his astonishing mercy was spoilt by the angry rebuke of a self-willed speaker.

Wiersbe: The remarkable thing is that God gave the water, even though Moses’ attitudes and actions were all wrong! . . . This account should warn us against building our theology on events instead of on Scripture. The fact that God meets a need or blesses a ministry is no proof that the people involved are necessarily obeying the Lord in the way they minister.

C. (:12-13) Judgment by the Lord to Exalt His Holiness

1. (:12) Severe Curse of Falling Short of Entering the Promised Land

a. Disbelief is the Root Problem

“But the LORD said to Moses and Aaron,

‘Because you have not believed Me,

to treat Me as holy in the sight of the sons of Israel,’”

b. Disqualification is the Tragic Result

“therefore you shall not bring this assembly into the land

which I have given them.”

2. (:13) Sad Commentary

a. Place of Contention – Provoking Moses to Sin While Contending with the Lord

“Those were the waters of Meribah,

because the sons of Israel contended with the LORD,”

b. Proof of Holiness – Providing Life-Giving Water While Protecting His Reputation

“and He proved Himself holy among them.”

Timothy Ashley: Yahweh showed his own holiness (thus the reflexive verb)—his separateness, power, in short, everything that made him God—in two ways. First, he showed it by giving water to his thirsty people and their animals. Second, he judged the sin of his trusted leaders Moses and Aaron. In doing so, he showed that everyone must fulfill his commandments, even (especially!) his leaders.

II. (:14-22) EDOM REFUSES PASSAGE

A. (:14-17) Diplomatic Entreaty by Moses

1. (:14-15) Record of Historical Hardship

“From Kadesh Moses then sent messengers to the king of Edom: Thus your brother Israel has said, ‘You know all the hardship that has befallen us; 15 that our fathers went down to Egypt, and we stayed in Egypt a long time, and the Egyptians treated us and our fathers badly.’”

Gordon Wenham: The request was couched in the form of a diplomatic letter that closely conformed to the conventions of oriental scribal practice, known from the archives of Mari, Babylon, Alalakh and El-Amarna. It consists of several standard parts. First, a mention of the recipient, King of Edom (14). Second, the formula Thus says. Third, a mention of the sender Israel and his rank, Your brother; ‘your servant’ is the more common phrase in diplomatic correspondence, but here a different phrase was preferred. Fourth, there is mention of Israel’s present predicament and their motives in making their request (15). Finally, the request itself (17).

Timothy Ashley: the misfortune (hattelā’â) — The root meaning of the word is “weariness,” hence “that which wears one out.” In Exod. 18:8 the word refers to hardships suffered between Egypt and Sinai, in Neh. 9:32 to hardships suffered in the history of Israel. In Lam. 3:5 the word refers to the ignominy of the defeat of Jerusalem in 587/86 and is paralleled to “bitterness” or “venom” (rō’š).

Ronald Allen: Moses believes that the experiences of his people were well known to the other nations of the region. He says to the king of Edom, through his messengers, “You know” (v. 14). This is a part of a significant issue in the story of the Exodus, that the saving work of the Lord was not done in a vacuum or in a hiding place. The nations round about were expected to understand something of what had happened, that it was the Lord who had brought deliverance for his people.

2. (:16a) Recognition of Divine Deliverance

“But when we cried out to the LORD,

He heard our voice and sent an angel and brought us out from Egypt;”

3. (:16b-17) Request for Uncontested Passage

a. (:16b) Makes Sense Logistically

“now behold, we are at Kadesh,

a town on the edge of your territory.”

b. (:17) Makes Sense from a Threat Assessment

“Please let us pass through your land. We shall not pass through field or through vineyard; we shall not even drink water from a well. We shall go along the king’s highway, not turning to the right or left, until we pass through your territory.”

Timothy Ashley: These verses contain the actual request for passage, based on all that has gone before, and Edom’s reply. It is interesting that the request does not divulge why the Israelites need passage through Edom, or their final destination. The pledge is that the Israelites will not go through Edom like a conquering army, much less like marauding bandits. Rather, they will act circumspectly by staying on the road. Of course, this is the language of diplomacy. The large number of Hebrews could not hope to cross through Edomite territory in one day, and one wonders where they planned to stay, what provisions they were to eat, etc. Whatever the answer to these questions, the gist of the message was that Israel will not be a burden on Edom.

B. (:18-20) Rejection by Edom

1. (:18) Initial Rejection Backed by Threat of the Sword

“Edom, however, said to him, ‘You shall not pass through us,

lest I come out with the sword against you.’”

2. (:19) Second Appeal Sweetened with Assurance of Payment

“Again, the sons of Israel said to him, ‘We shall go up by the highway, and if I and my livestock do drink any of your water, then I will pay its price. Let me only pass through on my feet, nothing else.’”

3. (:20) Final Rejection Backed by Show of Force

“But he said, ‘You shall not pass through.

And Edom came out against him with a heavy force,

and with a strong hand.”

Raymond Brown: Edom’s heartless resistance to Israel’s plea went down in history as a cruel rejection of God’s people. This godless refusal of a compassionate opportunity carries its own warning; present selfishness invites future judgment (24:18–19). The king’s callous words (‘we will … attack you with the sword’) came home centuries later.

C. (:21-22) Rerouting of the Journey

1. (:21) Acceptance of Rejection

“Thus Edom refused to allow Israel to pass through his territory;

so Israel turned away from him.”

Peter Wallace: So now they prepare to go around Edom (a long 90 miles to the south and then again around the southern and eastern borders of Edom). In other words, instead of 20 miles across Edom, they will now need to go 200 miles around Edom!

2. (:22) Arrival at Mount Hor

“Now when they set out from Kadesh,

the sons of Israel, the whole congregation, came to Mount Hor.”

(:23-29) EPILOGUE – DEATH OF AARON MARKS THE TRANSITION FROM THE GENERATION OF DEATH TO THE GENERATION OF PROMISE

“Then the LORD spoke to Moses and Aaron at Mount Hor by the border of the land of Edom, saying,”

A. (:24) Pronouncement of Judgment on Aaron

“Aaron shall be gathered to his people; for he shall not enter the land which I have given to the sons of Israel, because you rebelled against My command at the waters of Meribah.”

Gordon Wenham: Gathered to his people. This is the usual phrase to describe the death of a righteous man in a ripe old age. It is used of Abraham, Ishmael, Isaac, Jacob and Moses (Gen. 25:8, 17; 35:29; 49:33; Num. 31:2). By contrast it is a fearful mark of divine judgment to be left unburied and not ‘be gathered’ (Jer. 8:2; 25:33; Ezek. 29:5). But the phrase is more than a figure of speech: it describes a central Old Testament conviction about life after death, that in Sheol, the place of the dead, people will be reunited with other members of their family. As David said when Bathsheba’s baby died, ‘I shall go to him, but he will not return to me’ (2 Sam. 12:23). Thus, though both Aaron and Moses die outside the promised land, because of their sin at Meribah, that is the limit of their punishment. In death they are on a par with the patriarchs and other saints of the old covenant.

B. (:25-28) Transition in Leadership from Aaron to Eleazar

1. (:25-26) Preparation for the Death of Aaron

“Take Aaron and his son Eleazar, and bring them up to Mount Hor; 26 and strip Aaron of his garments and put them on his son Eleazar. So Aaron will be gathered to his people, and will die there.”

Dennis Cole: This was a momentous and emotional occasion for the nation and for Eleazar as they observed from a distance the departure of their first great high priest, the preeminent mediator of the sacral life of the nation in its relationship to Yahweh their God. For Eleazar it was no doubt a moment filled with emotional upheaval, a literal and metaphorical mountaintop experience in being inaugurated as the new high priest; but on the other hand it was a familial nadir, since his honorable father was about to die. The old era was passing; the generation was nearly gone that had witnessed the numerous miracles of God in Egypt, in the Exodus, at the Red Sea, at Mount Sinai, and all along the journey through the wilderness. A new generation of leadership was taking the reins over the nation and under God, and prospects of the new life in the Promised Land were looming ever nearer.

2. (:27-28) Passing of Moses and Transfer of Authority to Eleazar

“So Moses did just as the LORD had commanded, and they went up to Mount Hor in the sight of all the congregation. 28 And after Moses had stripped Aaron of his garments and put them on his son Eleazar, Aaron died there on the mountain top. Then Moses and Eleazar came down from the mountain.”

Gordon Wenham: The retirement of Aaron as high priest was a moment of vital significance in the life of Israel which had to be symbolized in the ritual stripping of Aaron’s high-priestly vestments and the investiture of his son, Eleazar. The high priest was the supreme mediator between God and Israel: the dignity of his office was expressed in the magnificence of his vestments. In a real sense the life of the nation was contingent on his carrying out his duties faithfully. Thus the death of a high priest marked the end of an era, and Numbers 35 implies it made atonement for some sins.

Raymond Brown; As Eleazar came down from the mountain, he was dressed in the garments of Israel’s high priest. The waiting community knew that, although they were under different spiritual leadership, the same ideals were guaranteed. God had made provision for the continuance of his people’s spiritual life by announcing that the priests’ responsibilities were to be shouldered by Aaron’s sons. Here was further visible evidence of the dependability of God’s word and his pledge to stay with his people forever. Israel’s circumstances would change and the context of their service vary enormously over the centuries, but obedient people would hand on his truth from one generation to another. The sight of Aaron’s appointed successor was further visible evidence of God’s unchanging provision, sovereign purposes and continuing presence. Only Aaron had left them, not God.

C. (:29) Mourning of the People

“And when all the congregation saw that Aaron had died,

all the house of Israel wept for Aaron thirty days.”

Timothy Ashley: This is the same mourning period as for Moses (Deut. 34:8). The normal time for mourning is seven days (e.g., Gen. 50:10; 1 Chr. 10:12; cf. Job 2:13). The prolongation of mourning shows the importance of the one who has died and the importance of the loss to Israel.

Wiersbe: Victorious Christian service, like the victorious Christian life, is a series of new beginnings. No matter what mistakes we’ve made, it’s always too soon to quit.